Open Garden: Be the ISP You Want to See in the World

As early as 2011, the United Nations declared that government restriction of Internet access is a violation of human rights and international law, and at least on paper universal access to the Internet is a part of member states’ Sustainable Development Goals. In the US, President Obama popularized the notion too, famously declaring that “broadband Internet is not a luxury, it’s a necessity.” Facebook and Google have also taken up the cause, understanding that getting more people online to see ads and buy things is necessary for their survival. Yet building the infrastructure globally for high-quality broadband Internet is not easy and connecting the other half of the world’s population will take time. Open Garden is among the new batch of companies aiming to offer a first line of connection in places where centralized ISPs are still unavailable or simply too expensive.

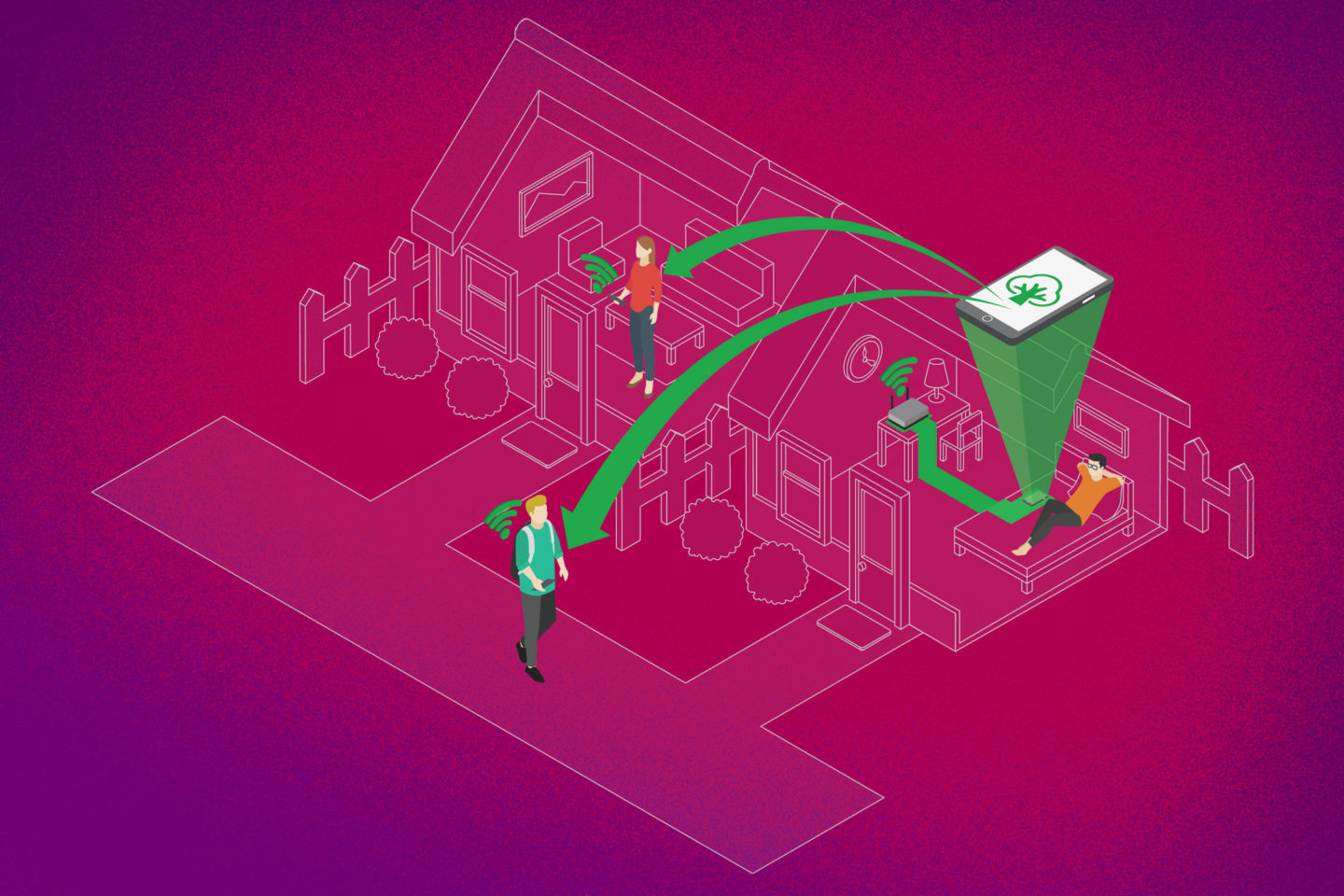

Paul Hainsworth, Open Garden CEO, puts it in terms we all understand by now: his company is Airbnb for Internet access, allowing anyone to become an ISP. Say your fee to Comcast or Verizon gives you up to a terabyte of high-speed Internet each month but you tend to use only half that. Using Open Garden’s protocols, you could reserve half your monthly data and sell it to others in your range – the apartment next store, for example. Essentially, a network of resellers becomes a decentralized layer of independent ISPs jutting out from nodes of hardline Internet access points. Eventually, Open Garden intends to work both on cellular and wifi networks. Some large centralized ISPs or cellular data providers could take issue with this, as Hainsworth acknowledged in our conversation, but ultimately it could be litigated as a matter of property rights – I bought this data, so why can’t I resell it?

One of Open Garden’s early supporters was Verizon Ventures, the VC arm of Verizon, which invested $3.5M last year. If it seems strange that a major telecom company would invest in a startup positioning itself a disrupter of telecoms, Hainsworth has an explanation: Verizon is actually happy to offload some of the burden on its own cell towers to hardlined wifi hotspots instead, such as those operated by resellers on Open Garden’s platform, particularly in areas with high network demands. But beyond this immediate operational benefit in high-traffic areas, major telecom companies could stand to benefit more structurally as Open Garden takes off. Users will now be able to sell excess data in chunks, at a cost per unit greater than we currently pay directly to ISPs. Think of your morning coffee: you can pay $4 at a cafe for a single cup, or a fraction of that at home with beans you’ve purchased at the store. Hainsworth refers to this as the “sachet” model: basically, if all we need is a small amount – just one cup of coffee, or just three megabytes of data – we’re willing to forego the savings possible in bulk. The established centralized ISPs may end up welcoming this too, since their direct customers could afford higher rates knowing they’ll recoup enough from reselling to their peer-to-peer network. The large ISPs may end up with fewer direct customers, but that means less need for customer service too – they can let the new decentralized mini-ISPs deal with the masses.

it seems strange that a major telecom company would invest in a startup positioning itself as a disrupter of telecoms”

Open Garden enables everyone to become a telecom profiteer, on the assumption that profit motive can incentivize you and me to push the frontier of Internet access where government policy and public will have not, even despite the UN and Obama’s efforts. Whether this will work depends at least in part on whether they can convince us that the OG token is a good place to store all this profit we’ll be raking in. At the very least, Open Garden will make sure that users can set a price, in their local currency, to ensure they can cover the actual cost of their data sold. Of course, the value of the coin will be a matter of ongoing supply and demand, but Hainsworth believes speculation will be a much more limited driver of value than other cryptocurrencies because the token is more like a utility to the system, integral for powering the decentralized ISP its users have created. While pre-sale accredited investors have claim to an undisclosed number of tokens, at least 35% of tokens have been reserved for incentivizing new users to bring the Internet to more places over a ten-year timeframe.

Open Garden also plans to use its technology to reach areas of the world that have less hardline internet connectivity by helping make cellular data available in smaller packets. Hainsworth envisions new mobile internet cafes cropping up, allowing shop owners to sell, in cash, small amounts of OG token to customers who may have never heard of a cryptocurrency wallet. These customers could then immediately redeem that crypto-pocket change by QR code for thirty minutes worth of data accessed through the shop owner’s Open Garden node. To make much of a dent, this model would require connections to a range of cellular providers and an integrated mobile payment system, and Open Garden hopes to have secured a relationship soon that will enable its operations in 130 countries with 500 mobile operators, reaching as many as 4 billion devices.

As tech startups continue the race to connect the unconnected, concerns over privacy, censorship, and net neutrality only increase. Facebook, purporting to bring the Internet to hard-to-wire places, has been criticized for providing instead only certain Western and corporate-friendly parts of the Internet on what it called its Free Basics app – and what some call “digital colonialism.” As the net neutrality debate has taught us in the US, connecting the whole world at the cost of an open Internet is antithetical to the initial promise of unfettered communication and information access. Luckily, Open Garden got its start as FireChat, one of the first practical decentralized mobile apps. It made its name in 2014 Hong Kong student protests, allowing protestors to communicate via a mobile mesh network even when cellular networks were overloaded. In its current iteration, Open Garden aims to maintain FireChat’s principles of censorship-resistance and privacy, building VPN services into its decentralized system. While its model still relies on central points of Internet connectivity and therefore is exposed to the politics and economics at play in corporate telecom, if Open Garden can insulate its layer of decentralization from censorship and shutdown attempts it could promise a better path toward global connectivity.

As early as 2011, the United Nations declared that government restriction of Internet access is a violation of human rights and international law, and at least on paper universal access to the Internet is a part of member states’ Sustainable Development Goals. In the US, President Obama popularized the notion too, famously declaring that “broadband Internet is not a luxury, it’s a necessity.” Facebook and Google have also taken up the cause, understanding that getting more people online to see ads and buy things is necessary for their survival. Yet building the infrastructure globally for high-quality broadband Internet is not easy and connecting the other half of the world’s population will take time. Open Garden is among a new batch of companies aiming to offer a first line of connection in places where centralized ISPs are still unavailable or simply too expensive.

Paul Hainsworth, Open Garden CEO, puts it in terms we all understand by now: his company is Airbnb for Internet access, allowing anyone to become an ISP. Say your fee to Comcast or Verizon gives you up to a terabyte of high-speed Internet each month but you tend to use only half that. Using Open Garden’s protocols, you could reserve half your monthly data and sell it to others in your range – the apartment next door, for example. Essentially, a network of resellers becomes a decentralized layer of independent ISPs jutting out from nodes of hardline Internet access points. Eventually, Open Garden intends to work both on cellular and wifi networks. Some large centralized ISPs or cellular data providers could take issue with this, as Hainsworth acknowledged in our conversation, but ultimately it could be litigated as a matter of property rights – I bought this data, so why can’t I resell it?

One of Open Garden’s early supporters was Verizon Ventures, the VC arm of Verizon, which invested $3.5M last year. If it seems strange that a major telecom company would invest in a startup positioning itself as a disrupter of telecoms, Hainsworth has an explanation: Verizon is actually happy to offload some of the burden on its own cell towers to hardlined wifi hotspots instead, such as those operated by resellers on Open Garden’s platform, particularly in areas with high network demands. But beyond this immediate operational benefit in high-traffic areas, major telecom companies could stand to benefit more structurally as Open Garden takes off. Users will now be able to sell excess data in chunks, at a cost per unit greater than we currently pay directly to ISPs. Think of your morning coffee: you can pay $4 at a cafe for a single cup, or a fraction of that at home with beans you’ve purchased at the store. Hainsworth refers to this as the “sachet” model: basically, if all we need is a small amount – just one cup of coffee, or just three megabytes of data – we’re willing to forego the savings possible in bulk. The established centralized ISPs may end up welcoming this too, since their direct customers could afford higher rates knowing they’ll recoup enough from reselling to their peer-to-peer network. The large ISPs may end up with fewer direct customers, but that means less need for customer service too – they can let the new decentralized mini-ISPs deal with the masses.

it seems strange that a major telecom company would invest in a startup positioning itself as a disrupter of telecoms”

Open Garden enables everyone to become a telecom profiteer, on the assumption that profit motive can incentivize you and me to push the frontier of Internet access where government policy and public will have not, even despite the UN and Obama’s efforts. Whether this will work depends at least in part on whether they can convince us that the OG token is a good place to store all this profit we’ll be raking in. At the very least, Open Garden will make sure that users can set a price, in their local currency, to ensure they can cover the actual cost of their data sold. Of course, the value of the coin will be a matter of ongoing supply and demand, but Hainsworth believes speculation will be a much more limited driver of value than other cryptocurrencies because the token is more like a utility to the system, integral for powering the decentralized ISP its users have created. While pre-sale accredited investors have claim to an undisclosed number of tokens, at least 35% of tokens have been reserved for incentivizing new users to bring the Internet to more places over a ten-year timeframe.

Open Garden also plans to use its technology to reach areas of the world that don’t have much hardline internet connectivity by helping to make cellular data more accessible. According to Hainsworth, “In much of Africa, mobile operators have bandwidth but insufficient demand because people can’t afford to pay for mobile services.” Allowing users to pay for just what they need could be the affordable option needed in these areas, where buying bulk is not feasible for many and where publicly funded options have lagged. Hainsworth can imagine a new generation of internet cafes cropping up, allowing shop owners to sell, in cash, small amounts of OG token via QR code to customers who may never even have heard of a cryptocurrency wallet. These customers could then immediately redeem that crypto pocket change for fifteen or thirty minutes’ worth of data from the shop owner’s Open Garden mobile node. It’s not there yet, but Open Garden is close to securing an agreement with a payments company that will enable users to in 130 countries to exchange the OG token for data on more than 500 mobile operators worldwide that together reach as many as 4 billion devices.

As the race to connect the unconnected continues, concerns over privacy, censorship, and net neutrality only increase. Facebook, purporting to bring the Internet to hard-to-wire places, has been criticized for providing instead only certain Western and corporate-friendly parts of the Internet on what it called its Free Basics app – and what some call “digital colonialism.” As the net neutrality debate has taught us in the US, connecting the whole world at the cost of an open Internet is antithetical to the initial promise of unfettered communication and information access. Luckily, Open Garden got its start as FireChat, one of the first practical decentralized mobile apps. It made its name in 2014 Hong Kong student protests, allowing protestors to communicate via a mobile mesh network even when cellular networks were overloaded. In its current iteration, Open Garden aims to maintain FireChat’s principles of censorship-resistance and privacy, building VPN services into its decentralized system. While its model still relies on central points of Internet connectivity and therefore is exposed to the politics and economics at play in corporate telecom, if Open Garden can insulate its layer of decentralization from censorship and shutdown attempts it could promise a better path toward global connectivity.

Comments