Meme Logic

How is a meme like a mushroom?

For most of modern history, it has been supposed that a piece of art is produced by an artist. We associate almost every cultural work — paintings, novels, films, and whatnot — with a single name. Even when the name is plural (“The Beatles”) or a stand-in for a collective (“Homer,” according to some), we still imagine that there is one person or group of people who hold(s) the authority to make all the important artistic decisions.

So much in our culture encourages us to think of ourselves as rational and autonomous. Needless to say this self-image is at odds with the lived experience of pretty much everyone. We like to buy into the vision of the autocratic artist because it supports the fantasy upon which societies rise and fall: the belief that there is someone, somewhere, who has total control over what they are doing.

Well, it’s 2018 and this fantasy is on its last legs. It’s time take a good hard look in the mirror and ask ourselves: How can we as a culture embrace our interconnected, mutually dependent, decentralized reality? What kind of art will we make? What kind of stories will we tell?

By way of an answer to these questions, I have a modest proposal: if you want to know the character of decentralized art, you need look no further than the common meme.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MEMES

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the word “meme” in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. The word “meme” comes from the Greek word mimema meaning “the imitated thing,” which Dawkins abbreviated because he wanted “a monosyllable that sounds a bit like ‘gene’.” According to Dawkins, examples of memes included “tunes, ideas, catchphrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches.”

Thirty-odd years later the meme of “meme” was re-appropriated to describe a much more specific unit of cultural transmission otherwise known as the image macro. These top-text/bottom-text pictures grew from the protozoic slime of the Something Awful forums. According to Know Your Meme, “In the forums, users could summon a number of default image macros using simple commands like [img – macro], for example, timelines, ‘Aces!’ and ‘Captain Obvious to the Rescue!’ images.”

Easy to make and share, image macros spread across the internet quickly becoming some of the earliest pieces of viral content. Meme formats evolved in tandem with the social media platforms that hosted them, branching out from image macros to audio, video, and other media. Each new addition into the meme canon introduced a greater degree of abstraction, pushing farther and farther away from the image macro format.

Unmoored from any single form, topic, or technique, the word “meme” has come full circle from when Dawkins originally described it as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” in 1976.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF MEME-ING

A meme is an inside joke that has been turned inside out. Anyone can access a meme, in the sense that anyone can make a contribution to any given meme simply by posting a new instance of it online. The totality of any given meme is an assemblage of self-similar elements; every meme is a continuously expanding collection of memes. This means that it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish an individual meme from the general class of which it is an instance.

The reason that we can describe both an individual Tide Pod joke (this Tide Pod meme) and the set containing every Tide Pod joke on the internet (the Tide Pod meme) is that memes are not produced in a linear, hierarchical way. They propagate laterally, moving in a self-directed fashion.

Memes do not spread according to any preordained plan. There is no central root-structure that determines where and how they develop. All a meme needs is the tiniest spore of an idea and substrate of to grow on, and it will bloom at an alarming rate.

Like a fungus.

EVERY MEME A MUSHROOM

Being able to grow without a central root is not the only way in which memes resemble mycelium. They also share with mushrooms a tendency to thrive in the dark. (They don’t call them “dank memes” for nothing.)

Consider the famous case of Pepe the Frog.

“Rare Pepes” originally consisted of silly, mostly apolitical riffs on a character from Matt Furie’s comic Boy’s Club. (Pepe’s first appearance in the series was in 2005.) But after spending enough time in the swampy cellars of 4chan, the Pepe spore was cross-contaminated with a virulent strain of white-nationalism and proto-fascism.

Members of the online communities where the hateful versions of these memes spread were derided as “normie” society. The forums where these people congregated became platforms for the spread of a new, post-ironic and highly toxic form racist and misogynist rhetoric.

By mid-2016, Pepe the Frog had been fully co-opted by the alt-right, a small but influential ideological movement which — like its meme networks — has no centralized structure.

MEMES EAT THE MAINSTREAM

These days memes are more popular than ever. They make us laugh, give us a brief respite from the horror show of the news, and the fact that they live online makes it easy for us to share this fleeting

succor with friends (and strangers) on the internet.

Why are memes are so weird, though?

Some people account for their strangeness by situating memes in the context of millennial comedic tastes, which tend to veer wildly toward the absurd. As The Washington Post’s Elizabeth Bruenig writes “[D]istortion is a key attribute of this form, a warping effect that occurs as each instance of a meme grows more distant from its origin, sometimes losing any meaning whatsoever… For millennials, memes form the backdrop of life.”

For Bruenig, the weirdness on display in memes (and millennial humor as a whole) is a way of mixing “relief with stress and levity with lunacy” in response to “the anxiety and dread of living in the postmodern world.”

Real meme-heads understand postmodern angst on an intuitive, cellular level. Most of the people who produce and proliferate memes on the internet are millennials or younger, which means that we grew up in a society obsessed with the idea of the future, yet largely unable to imagine it as anything but an extension of the neoliberal present. This implies the social and economic trends that define the contemporary moment — stagnant wages, mounting debt, increased isolation, rampant addiction, endless war, and a steadily warming globe — could last forever.

The anxiety this induces, on display in so many memes, doesn’t come from a fear of death so much as from a more or less unconscious sense that we are, in some way, already dead.

For mushrooms, dead matter is the beginning of a grand process of renewal. Fungi’s role in the ecosystem is to decompose organic compounds and release their nutrients back into the environment for other organisms to use. By metabolizing chemicals that other beings can’t, fungi are quite literally able regenerate life from death.

There is something toxic in our mainstream culture that prevents new ideas from taking root. We have a growing corpus of zombie-content — a shambling procession of sequels, prequels, and reboots on endless loop. To break out of the cycle, we will need to process this toxin and decompose the lifeless masses it has produced.

This is what memes already do.

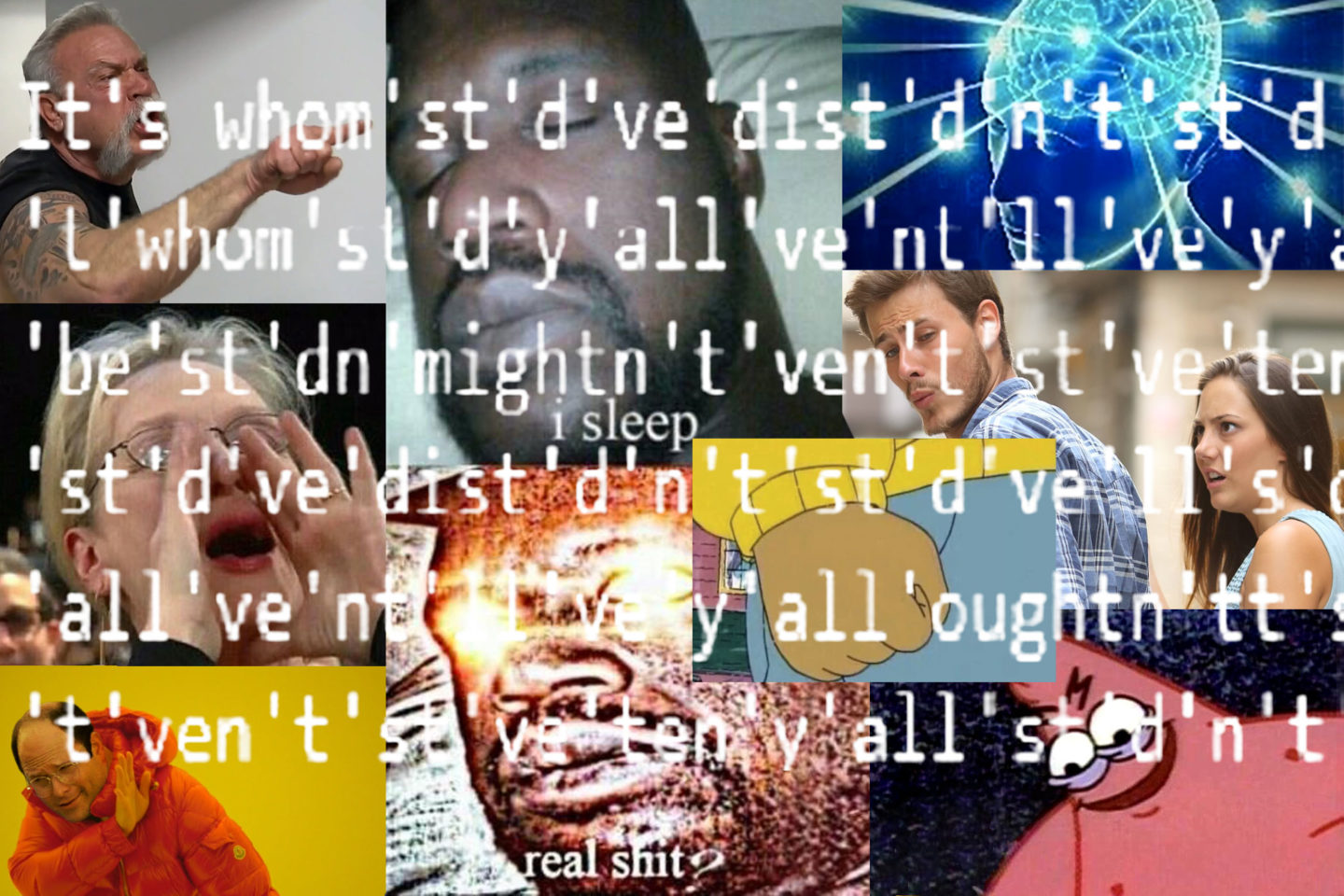

More often than not, memes tend to grow in the obscure, necrotic junk-space of pop culture. Characters from children’s cartoons and video games and slogans from outdated advertisements jostle for screen space with symbols from the institutions of religion, government, and press. Memes stick a dissident finger in the eye of decency and good taste, embracing crappiness for its own sake. Images are low-quality, pixelated, badly-cropped; when there sound (such as in Vine compilations) it is better for it to be clipped and distorted.

The crappiness of memes is not accidental. Everything illogical, grotesque, and debased in memes is more than an artifact of amateurism; it’s an essential part of how they function. Memes offer more than temporary respite from the grim indignities of life in an expired society. They are the fruiting bodies of a decentralized culture that extends much deeper, and is working to usher in something entirely new.

For most of modern history, it has been supposed that a piece of art is produced by an artist. We associate almost every cultural work — paintings, novels, films, and whatnot — with a single name. Even when the name is plural (“The Beatles”) or a stand-in for a collective (“Homer,” according to some), we still imagine that there is one person or group of people who hold(s) the authority to make all the important artistic decisions.

So much in our culture encourages us to think of ourselves as rational and autonomous. Needless to say this self-image is at odds with the lived experience of pretty much everyone. We like to buy into the vision of the autocratic artist because it supports the fantasy upon which societies rise and fall: the belief that there is someone, somewhere, who has total control over what they are doing.

Well, it’s 2018 and this fantasy is on its last legs. It’s time take a good hard look in the mirror and ask ourselves: How can we as a culture embrace our interconnected, mutually dependent, decentralized reality? What kind of art will we make? What kind of stories will we tell?

By way of an answer to these questions, I have a modest proposal: if you want to know the character of decentralized art, you need look no further than the common meme.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MEMES

Evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the word “meme” in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. The word “meme” comes from the Greek word mimema meaning “the imitated thing,” which Dawkins abbreviated because he wanted “a monosyllable that sounds a bit like ‘gene’.” According to Dawkins, examples of memes included “tunes, ideas, catchphrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches.”

Thirty-odd years later the meme of “meme” was re-appropriated to describe a much more specific unit of cultural transmission otherwise known as the image macro. These top-text/bottom-text pictures grew from the protozoic slime of the Something Awful forums. According to Know Your Meme, “In the forums, users could summon a number of default image macros using simple commands like [img – macro], for example, timelines, ‘Aces!’ and ‘Captain Obvious to the Rescue!’ images.”

Easy to make and share, image macros spread across the internet quickly becoming some of the earliest pieces of viral content. Meme formats evolved in tandem with the social media platforms that hosted them, branching out from image macros to audio, video, and other media. Each new addition into the meme canon introduced a greater degree of abstraction, pushing farther and farther away from the image macro format.

Unmoored from any single form, topic, or technique, the word “meme” has come full circle from when Dawkins originally described it as “a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” in 1976.

THE CONSTRUCTION OF MEME-ING

A meme is an inside joke that has been turned inside out. Anyone can access a meme, in the sense that anyone can make a contribution to any given meme simply by posting a new instance of it online. The totality of any given meme is an assemblage of self-similar elements; every meme is a continuously expanding collection of memes. This means that it can sometimes be difficult to distinguish an individual meme from the general class of which it is an instance.

The reason that we can describe both an individual Tide Pod joke (this Tide Pod meme) and the set containing every Tide Pod joke on the internet (the Tide Pod meme) is that memes are not produced in a linear, hierarchical way. They propagate laterally, moving in a self-directed fashion.

Memes do not spread according to any preordained plan. There is no central root-structure that determines where and how they spread. All a meme needs is the tiniest spore of an idea and substrate of to grow on, and it will spread at an alarming rate.

Like a fungus.

EVERY MEME A MUSHROOM

Being able to grow without a central root is not the only way in which memes resemble mycelium. They also share with mushrooms a tendency to thrive in the dark. (They don’t call them “dank memes” for nothing.)

Consider the famous case of Pepe the Frog.

“Rare Pepes” originally consisted of silly, mostly apolitical riffs on a character from Matt Furie’s comic Boy’s Club. (Pepe’s first appearance in the series was in 2005.) But after spending enough time in the swampy cellars of 4chan, the Pepe spore was cross-contaminated with a virulent strain of white-nationalism and proto-fascism.

Members of the online communities where the hateful versions of these memes spread were derided as “normie” society. The forums where these people congregated became platforms for the spread of a new, post-ironic and highly toxic form racist and misogynist rhetoric.

By mid-2016, Pepe the Frog had been fully co-opted by the alt-right, a small but influential ideological movement which — like its meme networks — has no centralized structure.

MEMES EAT THE MAINSTREAM

These days memes are more popular than ever. They make us laugh, give us a break from the horror show of the news, and the fact that they live online makes it easy for us to share this fleeting

succor with friends (and strangers) on the internet.

Why are memes are so weird, though?

Some people account for their strangeness by situating memes in the context of millennial comedic tastes, which tend to veer wildly toward the absurd. As The Washington Post’s Elizabeth Bruenig writes “[D]istortion is a key attribute of this form, a warping effect that occurs as each instance of a meme grows more distant from its origin, sometimes losing any meaning whatsoever… For millennials, memes form the backdrop of life.”

For Bruenig, the weirdness on display in memes (and millennial humor as a whole) is a way of mixing “relief with stress and levity with lunacy” in response to “the anxiety and dread of living in the postmodern world.”

Real meme-heads understand postmodern angst on an intuitive, cellular level. Most of the people who produce and proliferate memes on the internet are millennials or younger, which means that we grew up in a society obsessed with the idea of the future, yet largely unable to imagine it as anything but an extension of the neoliberal present. This implies the social and economic trends that define the contemporary moment — stagnant wages, mounting debt, increased isolation, rampant addiction, endless war, and a steadily warming globe — could last forever.

The anxiety this induces, on display in so many memes, doesn’t come from a fear of death so much as from a more or less unconscious sense that we are, in some way, already dead.

For mushrooms, dead matter is the beginning of a grand process of renewal. Fungi’s role in the ecosystem is to decompose organic compounds and release their nutrients back into the environment for other organisms to use. By metabolizing chemicals that other beings can’t, fungi are quite literally able regenerate life from death.

There is something toxic in our mainstream culture that prevents new ideas from taking root. We have a growing corpus of zombie-content — a shambling procession of sequels, prequels, and reboots on endless loop. To break out of the cycle, we will need to process this toxin and decompose the lifeless masses it has produced.

This is what memes already do.

More often than not, memes tend to grow in the obscure, necrotic junk-space of pop culture. Characters from children’s cartoons and video games and slogans from outdated advertisements jostle for screen space with symbols from the institutions of religion, government, and press. Memes stick a dissident finger in the eye of decency and good taste, embracing crappiness for its own sake. Images are low-quality, pixelated, badly-cropped; when there sound (such as in Vine compilations) it is better for it to be clipped and distorted.

The crappiness of memes is not accidental. Everything illogical, grotesque, and debased in memes is more than an artifact of amateurism; it’s an essential part of how they function. Memes offer more than temporary respite from the grim indignities of life in an expired society. They are the fruiting bodies of a decentralized culture that extends much deeper, and is working to usher in something entirely new.

Comments